Table of Contents

Open Table of Contents

Preamble

Best-in-slot (BIS) has been an issue long discussed since the beginning of TFT 5 years ago. Over time, the importance of BIS has been lowered, both as player skill has increased and as developers have tried to lower the power difference between getting good and bad items. There’s no other way about it: sometimes you get screwed by items in game, and those games really suck. Or at least, they used to. Item variance and output has generally been normalized, perhaps not to prevent, but at least to soften the blow of these situations. Instead of going 8th instantly when playing an AD comp with 3 rods, you can claw your way to a 6th!

You know, these aren’t even that bad.

However, this problem has somewhat remained with mana. Mana items are build-defining in a way raw damage has never been. While attack damage (AD) backliners can usually take a litany of assorted items, ability power (AP) backliners have been largely unplayable without some source of mana generation. All of their combat outputs are concentrated in their spell, and without being able to cast it multiple times a fight reliably, they simply cannot keep up with the innate high uptime of AD carries.

Furthermore, mana and damage differ mathematically. Damage comes from many different stats and sources, you can’t overcap on damage, and damage scales linearly. Mana’s place in TFT’s combat systems are at direct odds with each of these properties: mana has rather limited sources, mana only needs to hit specific thresholds, and mana generation is quantized. (Please excuse the gross oversimplification; each of these pillars has exceptions, but in general they tend to hold true for most units.)

At the same time, mana has historically been a space ripe for abuse. Mana lets AP champions participate in the game, but at the same time can easily remove other champions from doing the same. We’ve seen this throughout various sets—Shadow Blue Buff Ryze and LeBlanc, mana printer Sona, A.D.M.I.N., QSS Invokers Taric, Blue Battery and Axiom Arc—the list goes on. Mana has limited sources for good reason: spells are designed to be cast at noticeable intervals, and eliminating that time creates some less-than-stellar game states.

The difference in power between BIS mana generation and none was one of the largest in the game. This set, however, you may have noticed relatively few of these issues! Besides removing the particularly egregious edge case augments and traits, Riot has shifted mana design to lean into classes, changing units and items accordingly. In Set 10, mana generation was flattened across items. In Set 11, back line caster champions have maximum mana values to match their intended cast frequency. This, I argue (and to little dissent, tbh), has increased learnability and decreased the difference between mana items while still keeping their distinct purposes.

Unit Design

Why classes?

Classes are subcategories of unit classes that have similar outputs. Instead of forcing players to learn 16 different units and their precise mana itemization and various jibber jabber, classes allow players—and developers—to treat multiple units similarly. This increases learnability, as well as inter-composition flexibility by reducing opportunity costs for itemization.

The main difficulty with differentiating classes by maximum mana is in choosing the correct buckets. The impact of max mana varies based on class, most noticeably in backline AP casters. These units’ effectiveness depends heavily on multiple casts. They also don’t gain mana from taking damage, so thresholds are more fixed. Deviating from the max mana values above can have some adverse effects. For one, small decreases don’t really matter: mana resets to 0 once a spell is cast, so there’s no effect if you “overcap” on mana generation. Similarly, small increases can be huge nerfs in effectiveness: a change of 60 -> 61 mana is effectively the same change as 60 -> 70 mana, which is a 18% nerf to cast frequency in most cases.

Backline caster classes

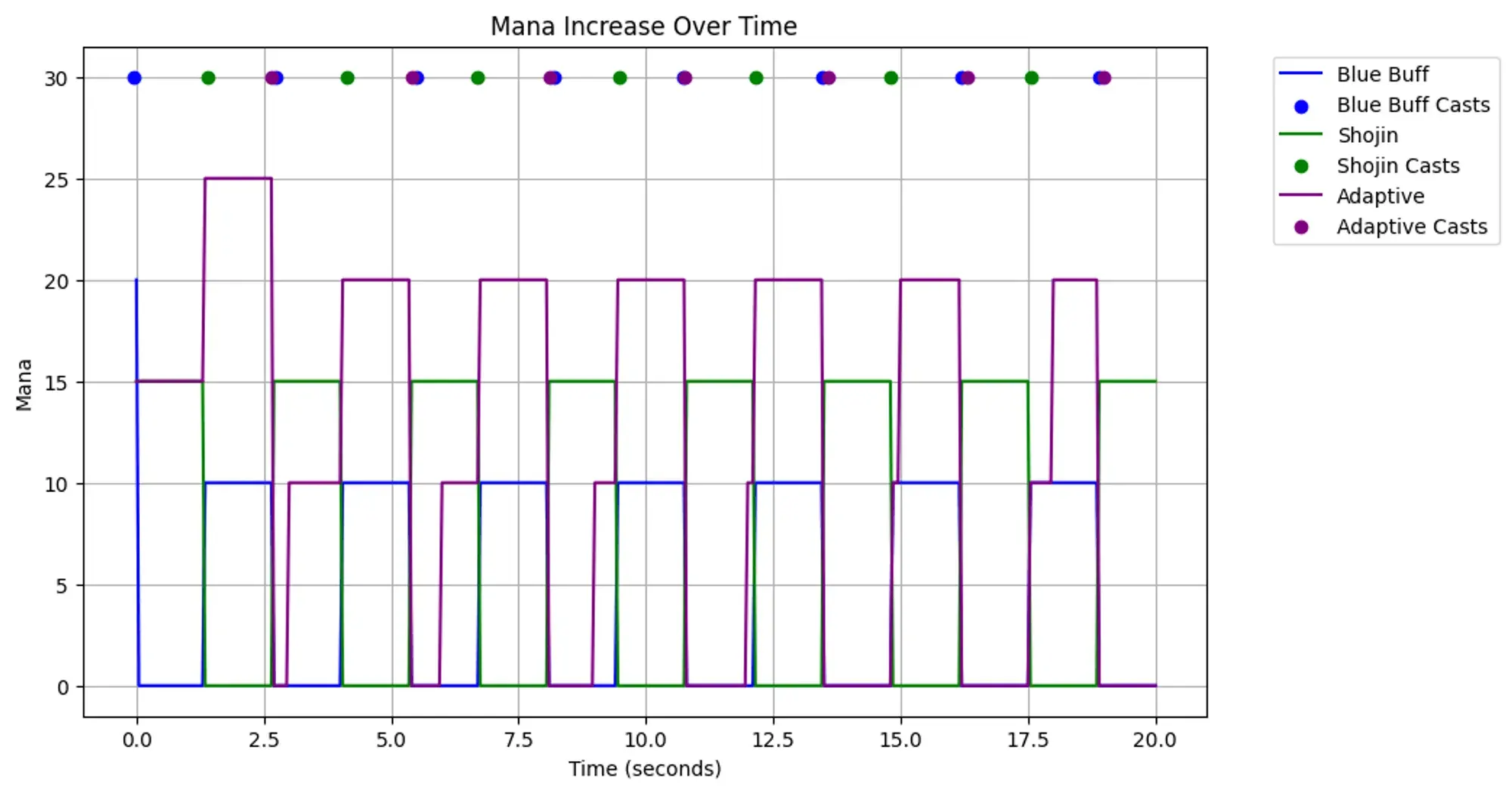

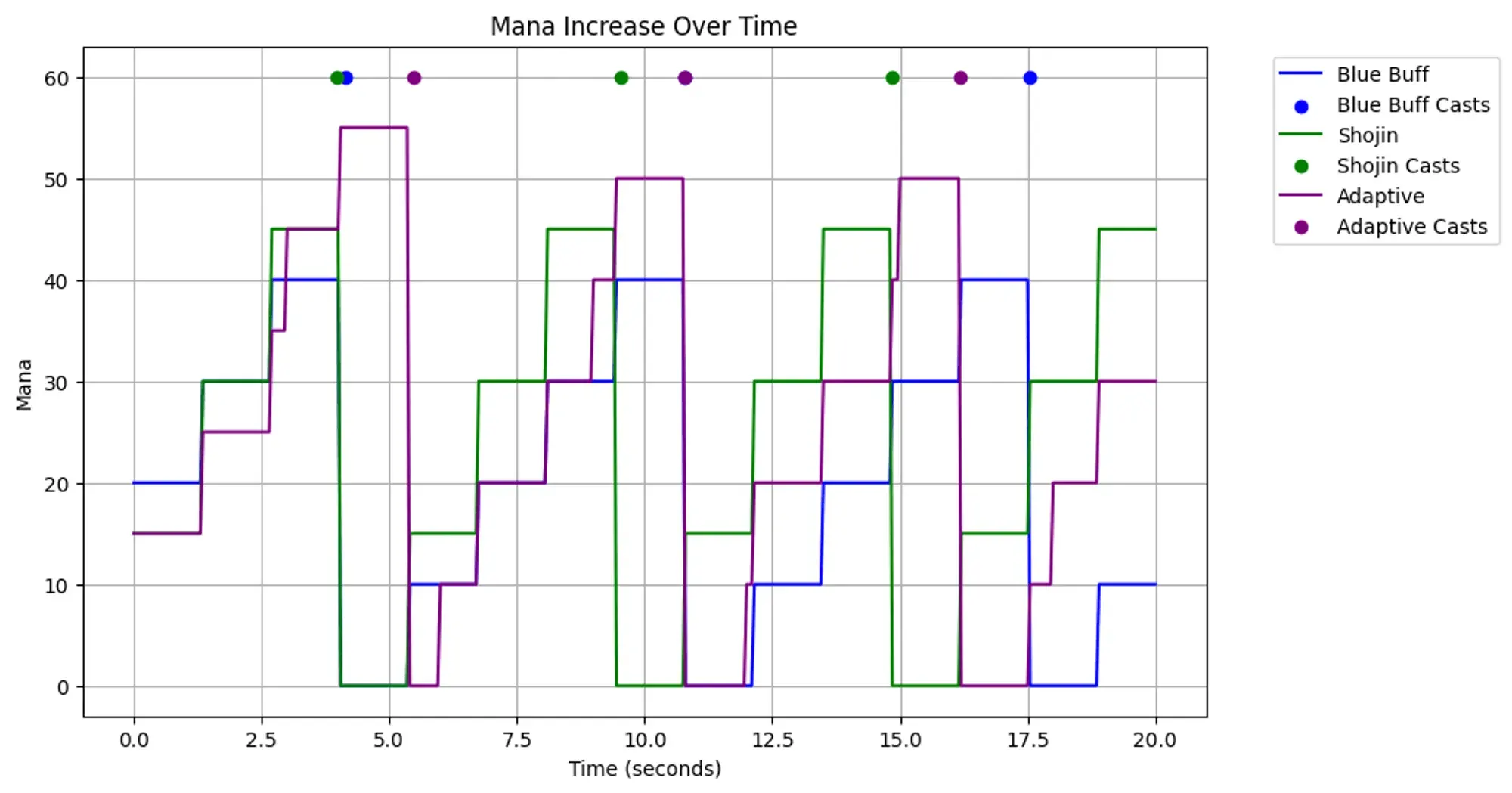

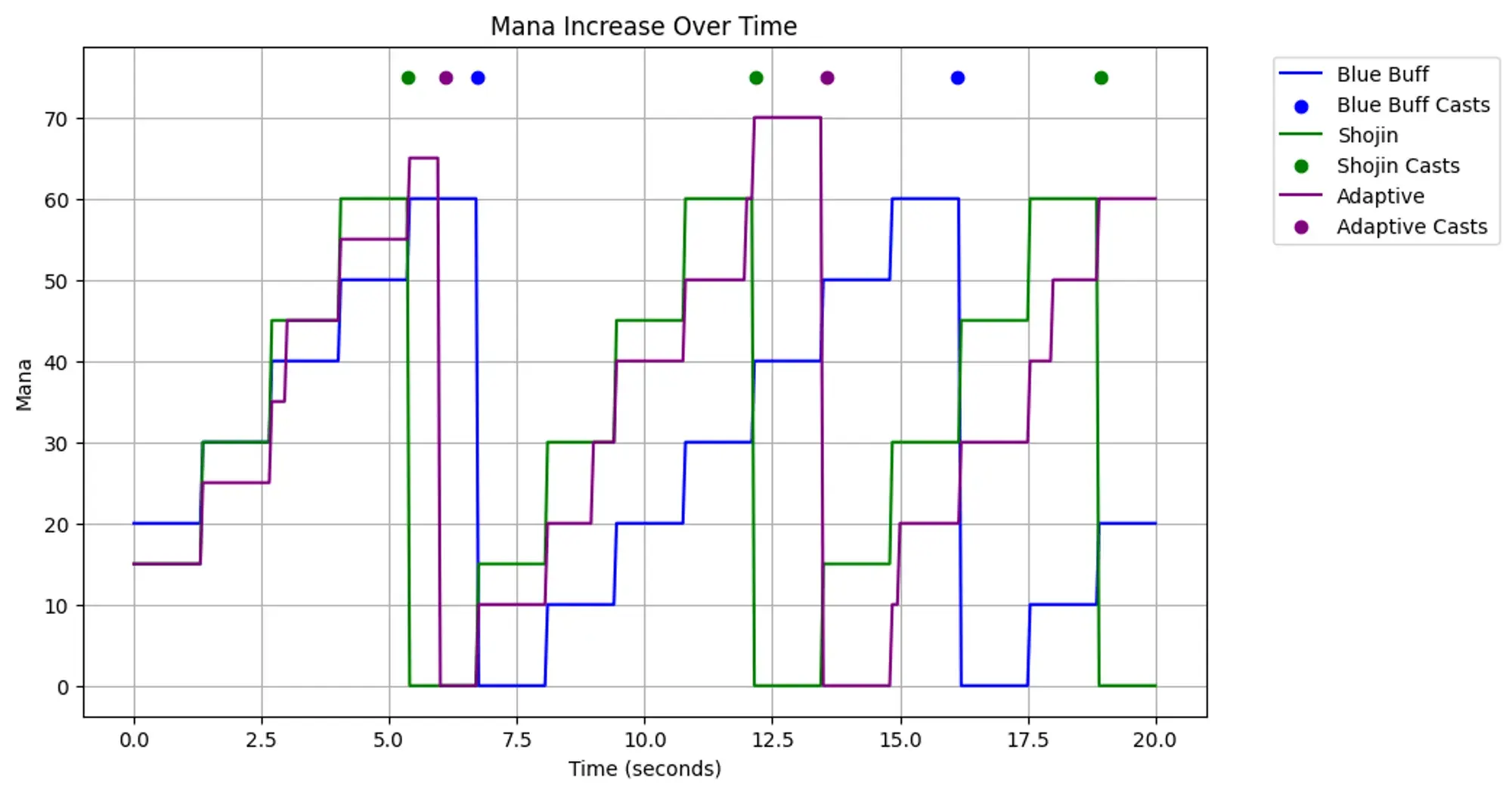

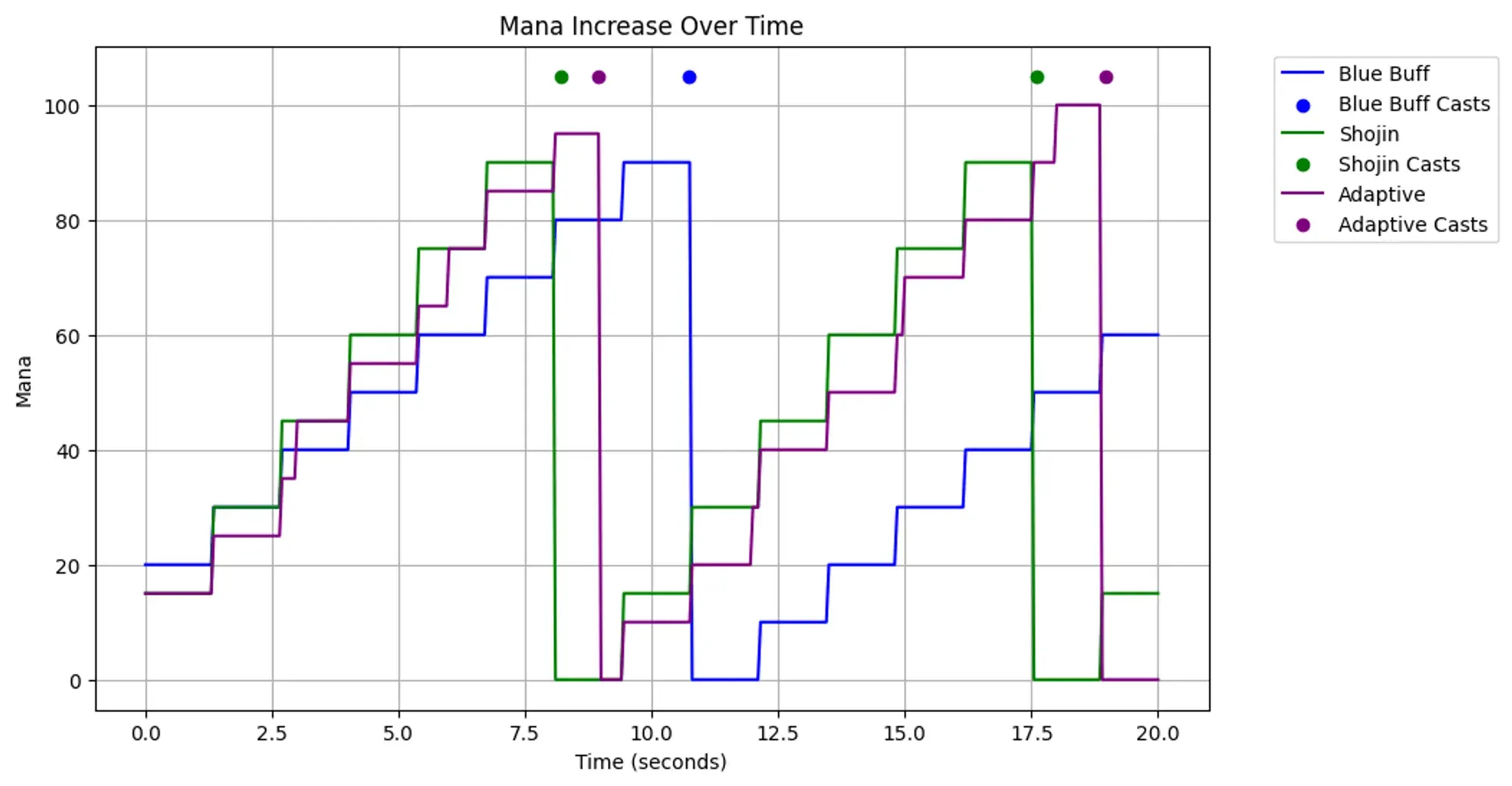

The following graphs simulate mana generation and unit casts, assuming a starting mana of 0 and an attack speed of 0.75. Large caveat: these do not account for the cast times and mana lock, but those numbers are not easily available and I’m basically just hoping they’re negligible (even though they definitely aren’t). I’ll link to my code at the end. It’s not particularly user friendly, but it’ll do. Hopefully.

30 mana: high frequency caster

This class of casters contains Teemo, Kog’Maw, Kindred, and Syndra. 30 is a convenient breakpoint because it makes equal use of Blue Buff, Shojin and Adaptive in making nice and tidy mana generations. The first auto attack generates half the mana, and the second generates the rest.

60 mana: medium frequency caster

This class of casters contains Ahri, Soraka, Zoe, Morgana, and Alune. These champions are in a sweetspot where Adaptive, Blue Buff, and Shojin all work similarly: Shojin and Adaptive get more casts, whereas Blue Buff can increase damage. For any generic AP unit, this is a nice middle ground. I suspect Riot puts units who they want to be particularly flexible with mana items, since BIS matters the least for this class of caster.

75 mana: medium+ frequency caster

This class of casters contains Lux, Zyra, and Janna. Blue Buff starts to lose a lot of value and Shojin starts to pull ahead, but Adaptive keeps up for a bit longer.

105+ mana: low frequency caster

The big casters. In this set, the only units here are 5 costs: Lissandra, Hwei, and Azir. Azir actually has his own category of mana, stuck down at a whopping 120 mana. That’s 12 autos without Shojin! These champions really only cast once or twice a fight without investment.

Case Study: Set 11 Lillia

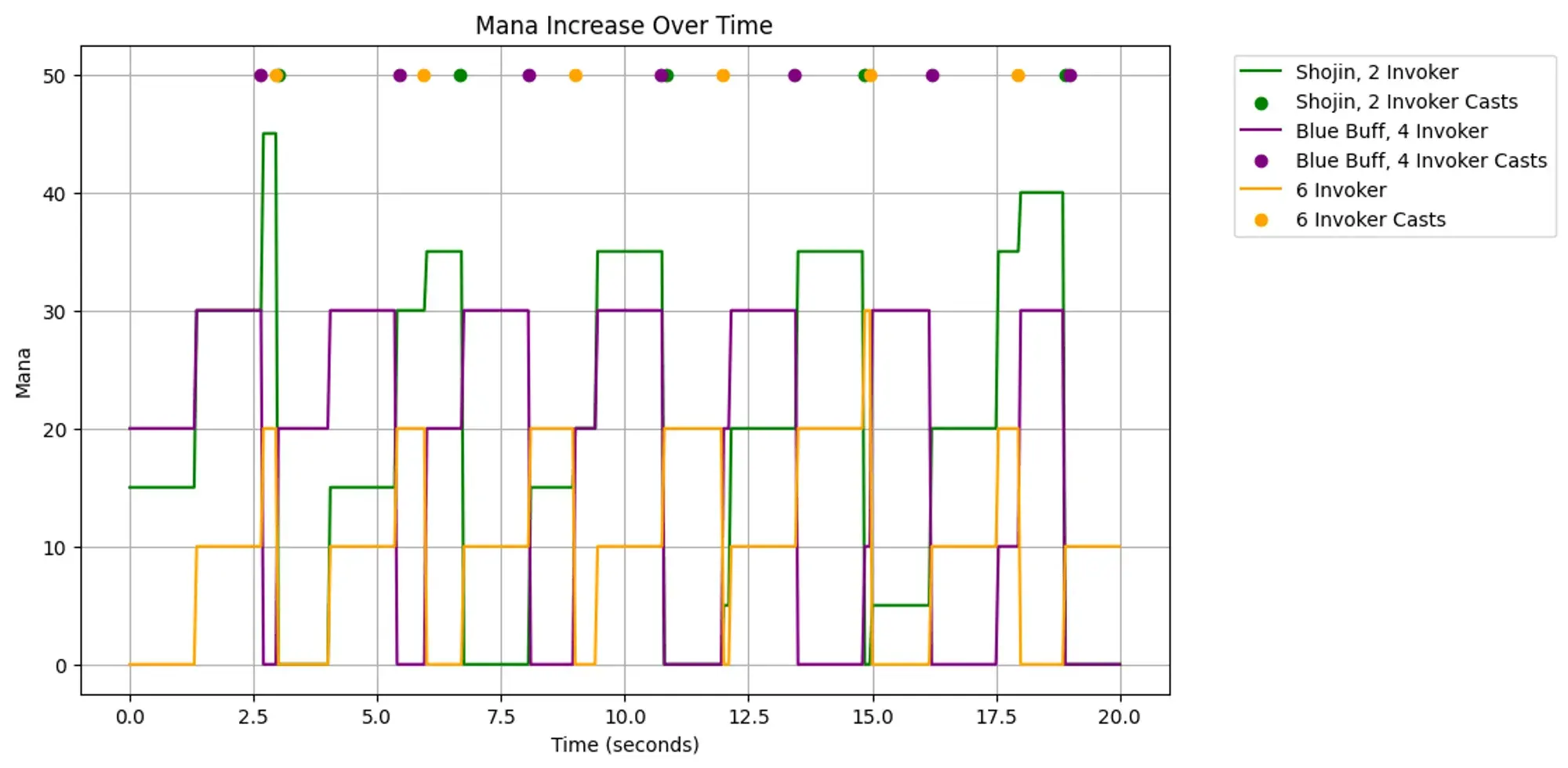

Lillia is the only champion who doesn’t fit neatly into these categories. This is almost certainly by design, and in a clever, understated way. As the community has figured out, Lillia has specific interactions with her Invoker trait that change her breakpoints. With 2 Invoker, she basically becomes a 45 mana unit, fitting nicely with Shojin to cast every 3 autos, whereas with 4+ Invoker, Blue Buff becomes superior. The forgotten sauce is with 6 Invoker. While the 6 Invoker board kinda sucks (lack of frontline), it does enable Lillia to drop a mana item altogether and still cast more than Shojin 2 Invoker.

Personally, I really like this sort of design. It does a few good things.

- It makes Invoker an intentional and impactful choice.

- Instead of hard binding Lillia to vertical Invoker, letting players opt into the Lillia lines that best suits their items without being overly restrictive adds a degree of flexibility to Lillia rarely seen. All are viable mana sources, just with tradeoffs.

- It creates a fun problem of BIS that is easy to account for and satisfying to solve.

- While BIS is not as important in terms of consistent ladder results, the fantasy of having the strongest board possible is something that is important to a game of variance like TFT. It’s fun to have a perfect idea of a unit or a board, and fun to obtain it!

Why these numbers in particular?

As much as I would love to ask the TFT designers directly, I do not work at Riot. My thoughts are that they’re somewhat arbitrary, roughly following a few guidelines.

- Make mana items a distinct choice with tradeoffs. A difference of 30 mana and 45 mana for classes isn’t quite enough room to distinguish cooldowns.

- Make cast downtime noticeable. Avoid 10 mana units to give players actual breathing room between casts.

- Spells should increase in reliability and/or impact as unit quality increases. Lower quality units cast less frequently (low reliability) with low impact. Higher cost units either scale up the frequency, or the impact, or both!

- Here’s where Azir comes in. Adding another unit to the board is one of the highest impact spell effects possible, so limiting the frequency of his cast is pretty important.

Further Notes

What about AD backliners?

AD backliners have less of an incentive to build mana items simply for the fact that their auto attacks do significant damage. Some AD champions are more heavily skewed in auto damage vs spell damage: Kai’Sa, for example, relies on her ability enough (shoutout to Trickshot) that she actually uses Shojin very well. AD champions who value high ability and auto attack uptime will often build Rageblade: look towards Aphelios and Ashe for examples. Finally, the last archetype of AD backliner relies on burst from their spell rather than repeated casts or high attack speed. The main candidates here are Senna and Caitlyn. Their spells are impactful, but need to threaten lethal damage all at once, not over a period of time. It should not come as a surprise that these carries are often rerolled.

What about frontliners?

Mana gain for frontliners is far messier. Damage taken grants mana, meaning frontline units—carry and tank alike—have more continuous mana growth. Thresholds aren’t as important here, and as such maximum mana is a real lever than won’t completely break a unit.

Something to note is how max mana tends to be doled out between carries and tanks. Mana generation through damage taken is calculated differently between pre-mitigation and post-mitigation. I’m not sure what the exact numbers are. They’ve changed throughout the years, and I don’t really trust the League fandom wiki, but I can say that post-mitigation damage taken generates significantly more mana than pre-mitigation. This is important because taking damage to generate mana should be risky. Tanks already have the advantage of survivability: they shouldn’t also be able to cast more than carries, especially when their spells tend to have higher impact per cast.

On that note, you tend to want melee carries to cast often. It’s fun, it’s interesting, and it pulls them away from being even higher variance oneshot machines. (There’s a whole essay about ranged versus melee in TFT and games overall, but that’s not important right now.) In contrast, tanks have a range of small and large mana pools. Area of effect crowd control is one of the strongest spell effects in the game, so frontliners with these abilities tend to have some of the highest mana pools. This set’s record holder is, predictably, Nautilus, at a delightful 170. Set 6 Galio, the 5 cost Socialite unit, had a mana pool of a whopping 300!

If you like Lillia so much, why not make every unit like Lillia? Why not marry her?

First, I don’t actually play much Lillia because piloting Lillia is difficult and I’m not that good of a player. Second, it’s just boring to make every unit the same, and it’s also not necessary to make every unit as nuanced. Third, she’s already taken.

tl;dr

Blue buff > shojin = adaptive for 30 mana

Shojin = adaptive > blue buff for 60 mana

Shojin > adaptive >> blue buff for 75+ mana

Lillia special case: Shojin for 2 Invoker, Blue Buff for 4 Invoker, mana not required for 6 Invoker

Here’s the code. Have at it. mana.ipynb

Conclusion

Mana is one of the more unique systems in TFT. Itemization and unit design, as such, is more formalized for mana, being relatively straightforward to model. More recent sets have leaned into mana “classes” to simplify the game and lessen the impact of BIS. This has made mana a particularly interesting system to analyze, and one that I think happens to be pretty elegant and complete. Thanks for reading!